Supporting children who have a missing loved one

- Lili Greer

- Nov 5, 2025

- 7 min read

Updated: Nov 15, 2025

When my mum Tina Greer went missing when I was thirteen, my world fell apart in ways that no one around me was prepared for. The days that followed were a blur and far from what you would imagine. I was interviewed late at night about what she was wearing, her partner, his house and the days leading up to her disappearance. I lived with my mum, so when she went missing I was essentially left without a home. I remember having to decide what to do with her things and then nothing else really happened. I was left to my own devices, waiting and wondering if she was alright. Deep down, I knew that if she hadn’t come back by now, something terrible had happened. There wasn’t much said about my mum or her case. Most of what I found out came through the media. The adults around me were doing the best they could. Like many families of missing persons, I was (and still am) trapped in uncertainty, desperate to know what had happened and where she is (Bernard, 2017; Maunganidze & ICRC, 2021).

The state of play

Families of missing persons are often left to navigate an unfamiliar kind of grief on their own. Grief is hard, but ambiguous loss is something else entirely. It’s the kind of grief families experience when a loved one is missing. It’s one of the most traumatic forms of grief a person can endure (Boss 2014 ). Yet families shoulder the brunt of this trauma with little support available (Maunganidze & ICRC 2021). The issue has largely been left to small charities and academics to pick up the slack.

As others have noted, talking about missing people "difficult exercise, one saturated with a range of feelings" (Parr and Stevenson 2015, p.289). So it’s not lost on me that we’re in foreign territory when it comes to supporting children and young people.

I do not claim to represent the experiences of everyone, nor am I a therapist. The experience of ambiguous loss can vary depending on a person’s age, their circumstances and their relationship to the missing loved one (Tao & Collins 2019). I’m simply sharing what would have helped me and what might help another young person going through the grief of having a missing loved one.

It goes without saying it’s important to take care of yourself. By looking after your own wellbeing, you’ll be in a better place to support any little people around you.

Hard questions

When we apply a bereavement lens it can help guide how we approach children who have a missing loved one. Being truthful in an age-appropriate way about what has happened or what hasn’t is really important. The Centre for Loss and Bereavement notes that euphemisms “interfere with a child's to opportunity to develop healthy coping skills that they will need in the future,” so avoid saying things like “they went on a holiday” or “they’ll be back.” Although it can feel uncomfortable, honesty builds trust. Eventually, the younger person will realise they’ve been protected with half-truths and feel betrayed (Boss, 2014).

Adults can sometimes think it’s in a child’s best interest to keep them shielded, but children in this situation often have just as many unanswered questions. By keeping information from children, adults can unintentionally make them feel even more helpless and out of control, which is common for those living with ambiguous loss (Lee & Whiting, 2007). I knew why my mum disappeared, but I wasn’t kept up to date on the investigation and it wasn’t really discussed at all. The unknown kept me up at night and having a conversation even though it would have been difficult would have really helped.

A common feeling among families I've interacted with of missing persons is that it’s better to be told there are no updates than to hear nothing at all. The same goes for children. Even a simple update, like “there is no new information,” is better than silence. You don’t have to go into every detail. For example, you could say “The police are still looking.”

If you’re unsure, ask whether they want to be involved. They might not and that’s okay. What matters is that they have some agency in the experience

.

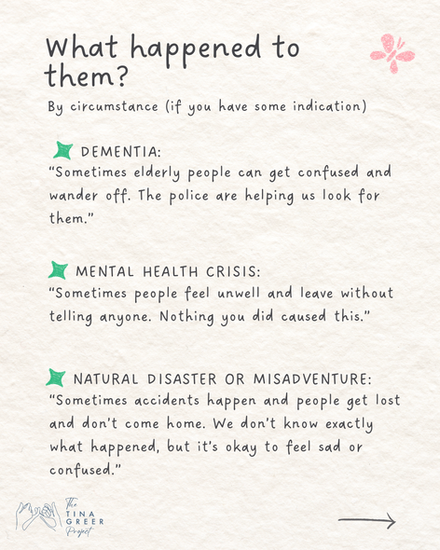

Here are some questions young people may ask, with suggestions of how you may like to respond.

Note: Boelen and Smid (2017) describe exposure interventions for prolonged and complex grief, which involve engaging with memories, meaningful objects, and places connected to the loss. While originally developed for complex grief, these strategies may also support children and families coping with the ambiguous loss of a missing loved one.

Preparing to face the world

For parents and carers, it can help to prepare the young person for questions they might face at school. Most missing persons cases get some media attention, as police often use media as a tool to assist in the location and recovery of missing persons. However, there is usually very limited information about the reasons for their absence (Siddiqui & Wayland, 2022), which in turn can spark questions and curiosity from others. For instance, at school I was asked abrupt questions about my mum, and my heart sank every time. Many of the questions I was asked I still don’t know the answers to. Being prepared for these conversations would have made a big difference to my wellbeing. Research shows that "human suffering can be lowered if the community as a whole acknowledges that the family’s anguish is justifiable"(Boss, 2014.p.4) giving children and their families a sense that they are not alone in their grief. One way to apply this is by letting the school know will help so the child/young person isn’t left to manage everything alone. It may be useful to have a conversation that acknowledges the missing person and their importance to the child and the community. Alternatively, if the child isn’t comfortable with this, a more general discussion about respectful boundaries, framed around “different family experiences” or “family dynamics,” could be held. This could include examples like illness, death or divorce. Framing it this way can help teach empathy and respect without singling anyone out.

Here are some questions they might be asked at school and possible ways to respond. Ideally, young people wouldn’t have to answer these types of questions at all. Still, it helps to have a plan and safe responses to use if needed.

For teens (and adults) it can also help to remind them not to read comments on news stories on platforms like Facebook or Instagram. The comments are usually upsetting, full of speculation and unhelpful.

Keeping their memory alive

As time goes on and public interest fades, it becomes even more important to make an effort to keep your missing loved one's memory alive. There are no set rituals for navigating ambiguous loss, and it cannot be fully “mastered”; the goal is not to eliminate suffering or to achieve closure, but to allow it to coexist with moments of joy (Boss, 2014, pp. 2–4; Boelen & Smid, 2017, p. 6). Simple acts like talking about them, revisiting memories, or honouring special dates such as birthdays make all the difference. Be real, and share that you miss them too.

One of the hardest parts for me was the limited time I had to know who my mum was. For younger kids, it can be helpful to write down what the person was (and is) like as well your favourite memories so they can revisit them. My mum’s childhood friend made me a scrapbook about my mum and their memories together.

When a loved one is missing, families miss out on the usual rituals that help mark a person’s life. Creating new ways to embrace meaning is important. Some families choose to hold a memorial or another type of ritual. For me, a significant step was holding a memorial for my mum. I had a plaque made and asked friends and family to write letters to her, which I placed where ashes would usually be laid. Whatever you decide, involve them in the planning. Let them pick a song, choose flowers or add their own touch.

Other ideas include:

Planting a tree or flower and naming it after the missing person

Visiting their favourite place on their birthday

Using the loved one's clothing to make a memory doll

Drawing, painting, telling stories, writing poetry or letters, making memory boxes or collages and playing music

In closing, supporting children and young people through the grief of a missing loved one is never easy, and nothing can take away the uncertainty. But adults play a crucial role in how young people make sense of that loss. By keeping memories alive, being honest, and creating small rituals or meaningful acts, families can stay connected to their loved one and begin to build resilience. Simple gestures make a difference, reminding children that their loved one is not forgotten and that they are not alone in carrying that uncertainty.

Helpful resources:

For children: In the Loop

For adults and professionals: Ambiguous Loss Master Class and The Hope Narratives

References

Bernard V. (2017). The disappeared and their families: When suffering is mixed with hope. International Review of the Red Cross, 99(905),475-485. doi:10.1017/S1816383118000577

Boelen, P. A., & Smid, G. E. (2017). Disturbed grief: prolonged grief disorder and persistent complex bereavement disorder. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 357.

Boss, P. (2014). Coping with the suffering of ambiguous loss. Professor Emeritus, University of Minnesota.https://app.mhpss.net/?get=288/boss-coping-with-the-suffering-of-al.pdf Center for Loss & Bereavement. (n.d.). How to support a grieving child. Bereavement Center. https://bereavementcenter.org/project/how-to-support-a-grieving-child/ Griefline. (2024, February 22). A gentle guide to self-care after loss: The E.A.S.T. approach. Griefline. https://griefline.org.au/resources/east-self-care-guide/ Holder, S. (2025, October 7). Expert cautions people using AI as search for missing boy in SA outback scaled back. ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2025-10-07/gus-missing-boy-facebook-ai-misinformation/105856594 Lee, R. E. & Whiting, J. B. (2007). Foster children’s expressions of ambiguous loss. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 35(5), 417-428.

Maunganidze, O. A., & International Committee of the Red Cross. (2021). Where are they?: Searching for missing persons and meeting their families’ needs. Institute for Security Studies. http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep62813 NSW Department of Communities & Justice, Families & Friends of Missing Persons Service. (2013). In the Loop: Young people talking about Missing. NSW Victims Services. https://victimsservices.justice.nsw.gov.au/documents/how-can-we-help-you/programs-and-initiatives/ffmps/In-the-loop.pdf Siddiqui, A., & Wayland, S. (2022). Lost from the conversation: Missing people, and the role of police media in shaping community awareness. The Police Journal: Theory, Practice and Principles, 95(2), 296–313. Parr, H., & Stevenson, O. (2015). ‘No news today’: talk of witnessing with families of missing people. Cultural Geographies, 22(2), 297–315. Tao, S., & Collins, J. (2019). Complex Loss in a Complex System: Ambiguous Loss in Child Welfare. Children’s Voice, 28(2), 6–20. The Missed Foundation. (2022). The Hope Narratives®. The Missed Foundation. https://missed.org.au/support/the-hope-narratives/

Wayland, S., & The Missed Foundation. (2023). Ambiguous Loss Masterclass: Ambiguous Loss 101. The Missed Foundation. https://missed.org.au/support/alm-ambiguous-loss-101/